My friend Shelli was the kind of bike friend we all have—I could never quite keep up with her. We once did a ride together in Pittsburgh; she rode her bike 140 miles from Cleveland, where we lived, in a single day. By herself. Just to do the ride the next day.

When she decided to move away from Cleveland to join her longtime boyfriend in the Seattle area, of course she wanted to make the trip by bike. I remember seeing her face beaming out from Instagram, in all her gear, squeezed next to some new friend she made while riding through Badlands National Park.

Then, just days later, came devastating news: Shelli had been hit by a car, from behind, that was traveling 60 to 65 miles per hour. That was almost a year ago. After months of hospital stays and surgeries, of fundraisers and rehab, Shelli finally completed her move, via airplane, in May.

“I was enjoying that trip immensely,” she said of her ill-fated ride. “I was almost here. I had a little detour, or a detour hit me.”

I'd heard about cyclists getting hurt or killed on cross-country rides. Bike and Build, an organization that gives young people the chance to ride across the country while raising money for Habitat for Humanity, has lost four riders since 2010. Ride Across America, a yearly cross-country marathon, has suffered two deaths since 2000. And that’s to say nothing of independent riders like Shelli, who go it alone or in small groups—nobody’s keeping an official tally on them.

RELATED: This Is What Happens When a Pampered Bike Racer Decides to Ride Across the Country

With local officials embracing (or at least paying lip service to) Vision Zero programs that would better protect cyclists and pedestrians, planners are getting smarter about preventing bike fatalities in urban areas. But until it happened to my friend, I always thought there was nothing we could do about catastrophic collisions on rural roads.

We don't know exactly how many people take long-distance bike trips every year, but we can make some rough guesses. The Adventure Cycling Association, which supports cross-country touring with specialized route maps and other services, has 53,000 dues-paying members. The organization sells 600 to 1,000 maps each year for its “Transamerica Trail,” which runs between Astoria, Oregon, and Yorktown, Virginia. The maps direct cyclists to routes selected for safety, scenery, and other amenities.

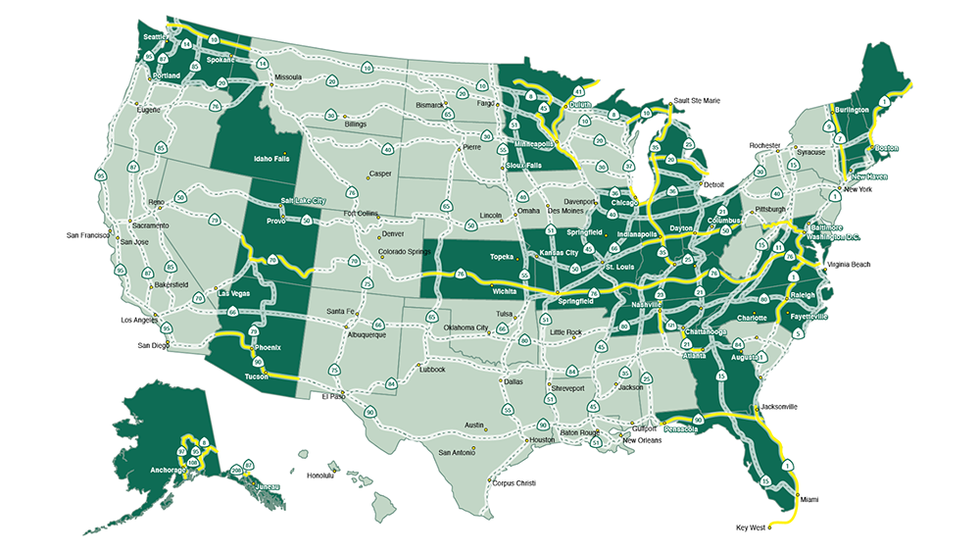

Transportation officials don’t recognize any of these routes. But that’s why the Adventure Cycling Association is also the key organizer of a bigger, more comprehensive effort that could help protect long-distance riders: the U.S. Bicycle Route System.

Modeled on the Interstate Highway System, this national network of bike routes creates a formal infrastructure for cross-country cycling. The association, working with bike advocacy groups, federal agencies, and state transportation departments, has been helping to piece it together for more than a decade.

Already, there are 11,526 miles of officially recognized U.S. Bicycle Routes, which at the very least have signs warning drivers to look out for cyclists. Potentially—depending on the commitment of state officials, budgets, and other factors—these routes can offer more concrete protections, like wider shoulders, narrower rumble strips, or even off-street bike paths.

“The idea is that drivers and cyclists alike will know that they’re on a bike route and watch out for each other,” said Saara Snow, the association’s travel initiatives coordinator.

RELATED: This Guy Rode Across America—On a Citi Bike

A contiguous cross-country route still doesn’t exist. But that goal, Snow said, is getting closer to reality.

Work on the U.S. Bicycle Route System first started in the late 1970s as a project of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). The first two routes were designated in 1982, but then 20 years passed without any additional progress.

During the mid-2000s, the effort was revived when AASHTO and the Adventure Cycling Association teamed up to develop a formal process by which states could apply for official bike routes. Since then the system has grown much more quickly, although gaps remain.

Colorado, for instance, interrupts Route 76/70, which will run from Virginia Beach to Los Angeles and will likely be the first truly cross-country route to open. The state has not yet prioritized designating national bike routes and it will likely take years of lobbying before an official commitment. And that’s before the design process even gets started.

Riding long-distance in a group? Learn how to safely stay at the front of the pack:

There isn’t any research telling us exactly how big of an impact these national bike routes will have on rider safety. But study after study has demonstrated a “safety in numbers” effect, wherein the more cyclists out on the roadways, the better the safety outcomes. A better, more complete system could inspire more cyclists to finally take on that cross-country trek. (Learn the skills you need to ride the roadways with The Complete Book of Road Cycling Skills.)

The National Park Service, meanwhile, is giving us a glimpse of how rural bike safety could go even further. On the Natchez Trace, a popular 444-mile trail through Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi, the agency has been conducting targeted PSAs to try to change the way drivers interact with cyclists.

None of this was advanced enough last year to help my friend. Though Shelli eventually made it to Seattle, she still spends a lot of time in various kinds of rehab programs. She said she’s looking forward to when she gets word—soon, hopefully—that she can ride again.