About John Tenniel’s illustrations

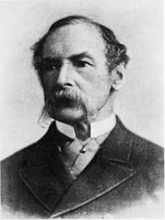

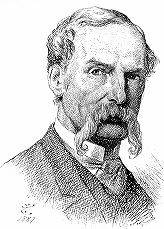

Sir John Tenniel, a well-known English illustrator and political cartoonist for the magazine ‘Punch’, made the illustrations for both Alice in Wonderland books.

About Sir John Tenniel

Sir John Tenniel was an English illustrator, graphic humorist, and political cartoonist. He was the principal political cartoonist for Punch magazine for over 50 years. Tenniel was born on 28 February 1820, and died on 25 February 1914. He was knighted for his artistic achievements in 1893.

Tenniel’s and Carroll’s cooperation

Author Lewis Carroll (Charles Dodgson), was rather fussy about how his book and the illustrations would look, so he provided Tenniel with many details and instructions.

Author Lewis Carroll (Charles Dodgson), was rather fussy about how his book and the illustrations would look, so he provided Tenniel with many details and instructions.

Tenniel at first refused when Carroll asked him to also illustrate his second book. When Carroll contacted illustrator Harry Furniss about illustrating “Sylvie and Bruno”, Tenniel alledgedly warned him about the author in a letter: “Dodgson is impossible! You will never put up with that conceited Don for more than a week!” (Jaques and Gidders) – although some think Furniss may have been exaggerating. Even though Carroll contacted many other illustrators, none of them met his standards or was willing to take on the work. Only after two and a half years of persuading, Tenniel finally agreed to also illustrate “Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there” as well, being it only ‘in the time he could find’.

Carroll had Tenniel alter his illustrations several times, for example when he was not happy with Alice’s face – even when the woodblocks were already engraved, which meant also the woodblock had to be (partly) re-done.

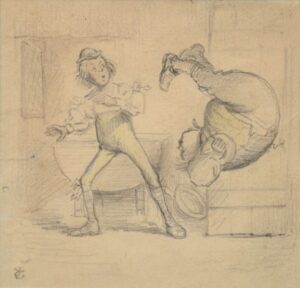

Lewis Carroll’s own design for Humpty Dumpty (Garvey and Bond, 63)

That doesn’t mean Tenniel’s illustrations were exactly what Carroll described they should be. Tenniel had quite a lot of freedom to give his own interpretation to the illustrations. On several occasions, Carroll was very much willing to accept the artist’s ideas, and in the illustrations the typical style of Tenniel is recognizable. Tenniel had some freedom in selecting the scenes to be illustrated (Hancher), and when Tenniel complained about having to draw a Walrus and a Carpenter, Carroll was willing to change the characters of his poem for him.

There also is evidence that Carroll did not even approve Tenniel’s sketches before they were being cut into the woodblocks. For example, Tenniel made 5 drawings of Alice wearing a chess-piece dress, and all the woodblocks showing them had to be plugged (partially repaired and re-done) because Carroll did not agree with it. (Demakos 2020 2)

The influence Tenniel had on Carroll is illustrated by the fact that Carroll recalled the first edition of his book, only because Tenniel expressed dissatisfaction about the quality of the printing of the pictures. Also, Carroll dropped an entire chapter from his book on Tenniel’s suggestion.

Tenniel may even have added his own subtle references in the illustrations: read about the origins behind Tenniel’s illustrations.

The making of the illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Initially, Carroll wanted to use his own manuscript illustrations for the official publication of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland“. However, he was discouraged to do that and eventually admitted that he needed a professional illustrator.

On the advice of Robinson Duckworth he chose John Tenniel to illustrate his book, and contacted him around 25 January 1864 through Tom Taylor, a friend at ‘Punch’ (Hancher 5). His initial intent was to order 12 woodblocks. At first, Tenniel was reluctant to take on the commission as he was busy with other projects. On 5 April 1864, Tenniel finally consented. The fee agreed was £138.

Carroll expanded the number of illustrations several times, as he realised that the value of a book would be associated with the number of illustrations. At one time, he planned for there to be 20 or 24 illustrations – a number that would be increased even more later (Hancher 130).

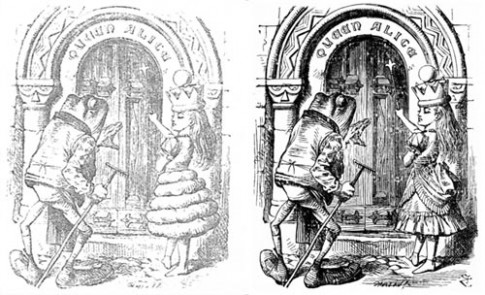

Rejected version of ‘Haigha in prison’ illustration (Hearn)

On 2 May 1864, Carroll sent Tenniel the first piece of slip set up for Alice’s Adventures. Tenniel’s first drawing on wood of the White Rabbit scurrying away from Alice was inspected by Carroll on 12 October 1864, and 34 illustrations were agreed.

On 28 October 1864, the Dalziel brothers showed Carroll proofs of several of Tenniel’s pictures. The cost for the engraving of Tenniel’s plates by the Dalziels was £142 for 42 plates.

On 8th April 1865, Tenniel was working on the 30th picture. By then, Carroll was still working on the final text for publication. Carroll sent the galley proofs for all the text to Tenniel on May 1865, so he could complete the illustrations. In the end, forty-two illustrations were completed – twice as many as Carroll initially anticipated. (Jones and Gladstone 253-255 and Jaques and Gidders)

On the website of Christ Church Library you can view Carroll’s illustration plan for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

The making of the illustrations for Through the Looking-Glass

Carroll worked much more in parallel with his illustrator for “Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there” than he did for “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, for which the illustrations were only drawn after the story was generally finished. This time, he already started looking for an illustrator in 1868, around the time he started on the actual writing of his sequel. While writing the text, Carroll determined exactly where the illustrations should go. He calculated the page numbers for the illustrations in advance, and determined the amount of space (the number of lines) that a picture would need, and made an extensive illustration plan.

Carroll wanted John Tenniel to also illustrate his sequel, but Tenniel initially refused, being busy and probably not willing to put up with the difficult author again. Carroll then contacted Richard Doyle, another illustrator for Punch, but Doyle was uncertain he could do it in time. Carroll kept trying to secure Tenniel, but on 8 April 1868 Carroll reported Tenniel’s warning that there was “no chance of his being able to do pictures for me until the year after next, if then. I must now try Noël Paton.”

However, on 19 May, Sir Joseph Noël Paton wrote that he was too ill and urged Carroll to persist with Tenniel. Carroll, in desperation, offered to pay Punch for his time ‘for the next five months’ to free him to illustrate the second Alice. In the meantime, he briefly considered William Schwenck Gilbert.

On 18 June 1868, Tenniel made what Carroll described as a ‘kind offer to do the pictures (at such spare times as he can find)’. Carroll accepted, but apparently it was still not all set, as he also contacted John Proctor about illustrating his book – who rejected. Tenniel’s services were finally definitively secured on the 1st of November. Tenniel hoped the illustrations would be ready by Christmas 1869. But indeed, he was so busy with other work that Carroll only saw the first ten rough sketches on 20 January 1870.

On 12 March 1870, Carroll and Tenniel met for two hours in London to set out the plans for 30 more pictures, having already sent three to the Dalziel Brothers at Camden Press for ‘cutting’.

Initially, the number of illustrations was set around 42, just like the amount in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. Over the course of time, this number was increased to 50.

Carroll sent the completed galleys, including the Wasp incident, to Tenniel on 16 January 1871 for pasting up and illustrating.

Tenniel’s illustration of the Jabberwock was originally intended as the book’s frontispiece, but on March 1871 Carroll decided to move the picture to the text pages and substituted the White Knight as the frontispiece on advice of his friends. Apparently, Carroll several times showed some of Tenniel’s illustrations to his friends before publication, to check what they thought of it.

According to Carroll’s illustration plan, the illustrations of Alice shaking the Red Queen into a kitten were originally planned to be placed back-to-back on the same sheet, so that when the pages was turned, the Queen changed into the kitten. However, Tenniel drew both illustrations in the same orientation, which made the effect impossible. Carroll eventually decided to put them both on left-hand pages instead (Wakeling, 28).

As of 25 April 1871, Carroll had still only received 27 pictures. Tenniel now hoped to complete them by July. This also did not work out, as the illustrations were not ready in time to have the book printed before Michaelmas. Therefore, it was decided that the book would be published right before Christmas 1871.

When it came out, Tenniel again was dissatisfied with the printing quality of the illustrations. Although Carroll suggested to Macmillan that the second batch of printed copies should be destroyed, this did not happen and no books were recalled (Jaques and Gidders 53).

Illustrations for ‘Alice’s Adventures Under Ground’

In the original manuscript of the book, Carroll drew his own illustrations. Carroll’s drawings of Alice were not modelled after Alice Liddell either.

It is suggested that he was inspired by paintings by his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti (modeled by Annie Miller) and his friend Arthur Hughes. Carroll owned Hughes’ oil painting ‘Girl with Lilacs’ (Stern).

On the last page of the original manuscript, Dodgson had stuck an oval photograph of Alice Liddell. An American Carroll expert, Morton N. Cohen, discovered that beneath the photograph lay a drawing of Alice from Carroll.

Illustrations for ‘the Nursery Alice’

For the ‘The Nursery Alice’, 20 of Tenniel’s illustrations were enlarged, colorized, and some of them were even slightly redrawn. Among others, Alice’s dresses were drawn with less crinoline. Tenniel hand-colored them. Dalziel’s signature has been removed from all Nursery illustrations.

For the ‘The Nursery Alice’, 20 of Tenniel’s illustrations were enlarged, colorized, and some of them were even slightly redrawn. Among others, Alice’s dresses were drawn with less crinoline. Tenniel hand-colored them. Dalziel’s signature has been removed from all Nursery illustrations.

Edward Evans created the woodblocks (multiple versions for each illustration, as each block was used to print a specific color) and colour-printed the book. The cover was drawn by Carroll’s friend and life-drawing teacher, E. Gertrude Thomson.

Carroll recorded in his diary on 29 March 1885, that twenty illustrations for The Nursery “Alice” ‘are now being coloured by Mr Tenniel’, and by 10 July he was able to report that ‘Mr Tenniel has finished the coloured pictures for The Nursery “Alice”‘. This means the illustrations were done well in time, as Carroll only wrote the text for the Nursery Alice in 1888 (Sibley).

Some doubt has been expressed as to whether Tenniel was personally responsible for the coloring of the illustrations to The Nursery “Alice”, largely because of the advertisement which appeared in the 1886 facsimile edition of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (and later in the 1887 ‘People’s Edition’ of Alice) that announced The Nursery “Alice” as “in preparation”: “Being a selection of twenty of the pictures in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland enlarged and coloured under the Artist’s superintendence, with explanations.” It seems likely, however, that this simply refers to Tenniel’s supervision of Edward Evans’ colour printing. (Sibley 92)

When The Nursery “Alice” was printed, Carroll rejected the first copies because of the coloring of the illustrations. He wrote the following to Macmillan, on June 23, 1889:

The pictures are far too bright and gaudy, and vulgarise the whole thing. None must be sold in England: to do so would be to sacrifice whatever reputation I now have for giving the public the best I can. Mr. Evans must begin again, & print 10,000 with Tenniel’s coloured pictures before him: and I must see all the proofs this time: and then we shall have a book really fit to offer to the public … The picture at p. 44 is enough by itself, to spoil the whole book!

The picture he referred to in the last line was the illustration of the Queen of Hearts pointing at Alice. Carroll thought her face was much too red (Gardner).

Tenniel’s original drawings remained black and white for over 40 years until 1911, when eight prints in each book were hand colored.

Woodblocks, electrotypes, and reproductions

According to Rodney Engen, Tenniel’s biographer, Tenniel’s method for creating the illustrations of the Alice books was the same as the method he used for Punch, namely preliminary pencil drawings, further drawings in ‘ink and Chinese white’ to simulate the wood engraver’s line, then transference to the wood-block (in reverse) by the use of tracing paper. The drawings were then engraved to the highest standards, in this instance by the Dalziel Brothers. Carroll appears to have ordered many (expensive!) changes to them.

The final stage in the reproduction process was to make copper-plated printing blocks from the wood-engravings, using them as masters. These so called electrotype blocks were used for the actual printing, to prevent damage to the woodblocks, which facilitated mass production and is the reason the original woodblocks for the ‘Alice’ books are still in good shape. The copper plates did wear, and had to be re-made several times as well, amongst others for the 1897 edition.

Because of the difficult process of creating wood-blocks involved, sometimes concessions had to be made as to the overall design of the illustration. For example, a character might be moved into a different position – which probably happened with the ape in the illustration of the Dodo with the thimble.

And, once wood had been removed, it could not be put back without a great deal of difficulty. A small number of Alice wood-blocks have had alterations or repairs made to them, that are in some cases detectable from the proofs which have been taken directly from the blocks. For example, the wood-block of the Hatter at the trial scene, the section showing the Hatter’s cup with a piece bitten out, had to be repaired and re-engraved (Wakeling).

Notes and corrections by Tenniel on a proof of an illustration (Garvey and Bond, 74-75)

When Carroll recalled the first 2000 copies of his book and had another printer re-do them, the new printer (Clay) reset all the letterpress, but re-used the electrotypes blocks made for printing the illustrations by the original printer (The Clarendon Press) (Hancher 211).

From the 6th edition of the book on, the text of the story was also electrotyped. It is unknown whether these electrotypes were made from just letterpress and electros of the illustrations were then juxtaposed to them, or that an entire page, including the illustrations, was made into an electrotype (Hancher 206).

In 1896 Carroll ordered new electrotypes to be made from the original woodblocks for the 1897 edition, because the first electrotypes had become worn. He had the old electrotypes destroyed to prevent piracy (Demakos 2021 34).

Many of Tenniel’s preliminary drawings have survived. They are catalogued in Justin Schiller’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: An 1865 Printing Re-described and Newly Identified as the Publisher’s ‘File Copy'” (privately printed (Jabberwock), Kingston, NY, 1990).

In 1981, the original wood-blocks were discovered in a bank vault where they had been deposited by the publisher. They are now at the British Library (Jones and Gladstone 252).

Also, more than 150 electrotypes have survived and sometimes appear at auctions. It is very hard to determine for which editions they were actually used though (Hancher 207).

In 1932, a Lewis Carroll centenary edition of the ‘Alice’ book was published, for which the illustrations were re-engraved in woodblocks (which probably were electrotyped subsequently). Many subsequent editions of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (including Gardner’s “Annotated Alice”) do not use the original Dalziel blocks, but these reproductions instead! It is very hard to recognize a reproduction from an original, but clues are:

- The addition of Tenniel’s own monogram (which originally lacked) to the lower right corner of the frontispiece illustration;

- A very small addition of the name of the new engraver (Bruno Rollitz) to Tenniel’s monogram, in four of the illustrations (Alice with the puppy, the Queen of Hearts confronting Alice in the garden, Alice overturning the jury box, and Alice with the shower of playing cards).

(Hancher 237)

Mistakes in the illustrations

Tenniel made some mistakes in his illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

- In chapter 1 we are told: “[…] she found herself in a long low hall, which was lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof.” In Tenniel’s illustration of Alice and the White Rabbit running through this hall, no lamps are visible however.

- Compare Tenniel’s first drawing of the White Rabbit with his second one. In the latter, the Rabbit’s vest is checked just like his jacket. Besides this mistake, the Rabbit also should be wearing his court outfit by now, as we are told in chapter 2 that he returned ‘splendidly dressed’, which means his outfit isn’t the same one as the one Alice first saw him in when checking his pocket watch.

- When Alice meets the Cheshire Cat sitting in a tree, he vanishes and reappears again at once. When Alice walks on, he reappears again on a branch. This time, he disappears more slowly, on Alice’s request. However, the picture of this slow vanishing shows the Cheshire Cat sitting in exactly the same tree as he was in when Alice met him before walking on.

- In two illustrations, the Hatter’s bow tie has a pointed end on his left. In a later illustration, the pointed end is on his right.

- The Queen of Hearts’ dress is in fact not modelled after the outfit of a 19th century Queen of Hearts playing card, but the dress of a Queen of Spades card (Hancher)! It is unclear whether Tenniel intentionally chose another suit as a model for the queen’s outfit.

Then there is the curious case of Alice’s missing face in the illustration of her and the Cheshire Cat in the tree. In several editions, we only see her hair, not her profile. This is possibly a mistake made by the printer when creating woodblocks for the illustrations, that was discovered and corrected only quite some time later. It concerns the following editions (Goodacre, 110):

- Standard “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” editions: 84th thousand (1891) until the revised 86th thousand (1897).

- “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” People’s Edition: 23rd thousand (1891) until after the 29th thousand (1892)

- The Nursery Alice: the 1890 printing (see an example)

Also in “Through the Looking-Glass”, some errors were made:

- In “Though the Looking-Glass”, the illustrations show the Kings wearing the same crowns as the Queens. Kings are supposed the have crowns with a cross on top. It is unsure whether this is a mistake in the illustrations, or perhaps a request from Carroll to remove any possible references to Christianity?

- Also, read the passage of the chapter about Tweedledum and Tweedledee, when they are preparing for the fight. It says that Tweedledum has a saucepan on his head, and that, when they are finished with dressing, Tweedledum will get the sword and Tweedledee the umbrella. But when you look at the picture, it is Tweedledee who has the sword, and he already has it while Alice is still busy dressing them. I’m also wondering about the bolster she put onto Tweedledee’s neck; is the bolster perhaps the thing that Tweedledum is wearing below his saucepan…?

- According to Lewis Carroll, Tenniel also drew the rattle the wrong way. In a letter to Henry Savile Clark, dating November 29, 1886, Carroll states that Tenniel had drawn a watchman’s rattle (used to sound an alarm) in stead of a child’s toy rattle. He was certain that the latter was meant in the old nursery rhyme (Gardner 227).

There are also some inconsistencies between the enlarged and colored illustrations of The Nursery Alice, which are partly caused by the fact that the cover image was drawn by E. Gertrude Thomson in stead of John Tenniel:

- In three of the images Alice retains the double-line of stitching at the bottom of her dress, but in others this has been omitted.

- During the baby-pig episode, the ribbon adorning its cap changes from blue to red.

- The White Rabbit’s jacket morphs from orange in the image from the opening of chapter 1 to red on the book’s front cover.

- In the cover image, the White Rabbit’s waistcoat is replaced with a green scarf and the March Hare is also dressed differently.

Works cited

Demakos, Matt. Cut-Proof-Print. From Tenniel’s Hands to Carroll’s Eyes. Stuffing the Teapot Press, 2021.

Demakos, Matthew. “Sketch-Trace-Draw. From Tenniel’s Hands to Carroll’s Eyes, Part 1”. Knight Letter, volume III, issue 4, no. 104, spring 2020.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. 150th anniversary deluxe edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Garvey, Eleanor M. and W.H. Bond. Tenniel’s Alice. Drawings by Sir John Tenniel for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Harvard College Library and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978.

Goodacre, Selwyn H. “The Nursery “Alice” – a bibliographical essay”. Jabberwocky, volume 4, issue 4, Autumn 1975.

Hancher, Michael. The Tenniel illustrations to the ‘Alice’ books. The Ohio State Press, second edition, 2019.

Hearn, Michael. “Alice’s Other Parent: Sir John Tenniel as Lewis Carroll’s Illustrator”. American Book Collector, May/June 1983.

Jaques, Zoe and Eugene Gidders. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. A Publishing History. Ashgate Studies in Publishing History, Ashgate Publishing, 2016.

Jones, Jo Elwyn and J. Francis Gladstone. The Alice Companion. NYU Press, 1998.

Sibley, Brian. “The Nursery “Alice” Illustrations”. Jabberwocky, volume 4, issue 4, Autumn 1975 .

Stern, Jeffrey. “Lewis Carroll the Pre-Raphaelite”. Lewis Carroll Observed, by Edward Guiliano, Clarkson N. Potter, 1976.

Wakeling, Edward. “John Tenniel (1820-1914)”. March 2008, www.wakeling.demon.co.uk/page10-Tenniel.htm.