For Doisneau, 1947 was a landmark year. First of all, there was the birth of his second daughter, Francine. It was also the year in which he received the Prix Kodak, a prize awarded to promising young photographers. And it was the year when he met Jacques Prévert and Robert Giraud: two extraordinary personalities, two flâneurs who transformed his vision and field of investigation, showing him a new Paris by day and by night. It was on one of his reportages at Saint-Germain-des-Prés that Doisneau met Prevert. He immediately fell under the poet’s spell and the two became firm friends, going on long, meandering walks through the city and especially through the popular quartiers. ”What I know of the dreamlike and fantastic, I owe to Prevert,” Doisneau observed, adding: “Prevert took over the words that everyone else had given up on and displayed their flamboyant, fantastical qualities. That kind of thing could be transposed; I could make images on the same basis.” Doisneau loved Prevert’s words and Prevert loved Doisneau’s images. “When he (Doisneau] goes slyly about his work, he does so with a sense of fraternal humor; there is no superiority complex when he sets out his bird-catcher’s lures, his poacher’s snares. With him, the verb ‘to photograph’ is always conjugated in the imperfect lens of the objective.”

A second encounter that was to play a decisive role in Doisneau’s life took place in the gallery on the Rue de Seine managed by Robert. with whom Doisneau collaborated sporadically for the magazine Point de Vue – Images du Monde. Robert Giraud was one of the eminences of Parisian nocturnal life. ‘Without him, I should never have known the thieves, the tattooed, the nightnurses of love and a whole population of uncategorizable individuals.”

In Albert Fraysse’s bistro, almost next door to the gallery; Giraud, with elbow on the bar, recounted his nocturnal adventures at Les Hailes, Maubert, or rue Mouffetard. A little later, these adventures were to he the inspiration for a book, Le vin des rues; Prevert provided the title and Doisneau the photos. Giraud was the poet of nightlife and introduced Doisneau to the world of the night, to the homeless and the beggars and dropouts of every kind: “In short, a tribe that surfaces at a time when honest folk are taking to their · beds.”

Doisneau was able to use Giraud’s and, in particular, Rami’s · encounters and discoveries to illustrate articles on this or that subject and offer them to the press: Paris-Presse, Point de Vue – Images du Monde, Cavalcade; Regards, and so on. Chez Fraysse was also the rendezvous of regulars such as Jean-Paul Clebert, Michel Ragon, the brothers Jacques and Pierre Prevert, Maximilien Vox, Cesar, and Maurice Baquet, who became one of Doisneau’s closest friends. The photographer had just been taken on by Vogue and sought relief at the bistro. “At the time, I was playing at being a fashion photographer but I didn’t enjoy it very much. To avoid any tincture of depression, every evening I sought the indispensable antidote at the bar of this café-tabac.”

Doisneau’s encounter with the cellist Maurice Baquet, a member of the Prevert “gang,” was another decisive moment. “When our paths crossed, I found my instructor in happiness … I took such pleasure in his teaching that I enrolled for thirty years on his refresher course, a necessary preliminary in making the book that served as a pretext for our meetings.” The friendship struck up at their very first meeting gave rise to the idea of a book composed of little humorous scenes, all of which involved a cello. The first shots for this book were taken in 1949 and the process continued over several decades; publication finally occurred in 1981, under the title Ballade pour violoncelle et chambre noire (Ballad for Cello and Camera obscura). An excellent musician, a remarkable comedian, a master of wit and the incongruous. Baquet could let his hair down with Doisneau, who delighted in his friend’s drollery Both were already widely published and their complicity led Baquet to pose as a model for some of the publicity photo- staged by his friend.

On the advice of Raymond Grosset, Doisneau agreed to spend four days a week from 1949 to 1951 as a photographer at Vogue, then edited by Michel de Brunhoff. This was mainly fashion photography but also reportages, sometimes undertaken with the writer Edmonde Charles-Roux, who notes that “Doisneau was the only reporter of Parisian life. I wrote, he illustrated. Together, we would comb through the cafes-theatres, the scenery workshops, the dance studios. the boxes and corridors, the studios of the famous painters and the country houses of the greatest writers.”

Into this kaleidoscopic range of imagery; Doisneau managed to sneak a few personal photographs like his series on Parisian pigeon, Parisian concierges, and portraits of celebrities. With the exception of these invaluable gleanings, the world of fashion and wealth left him completely cold. High-society soirees were utterly alien to his interests: “drowning in syrupy-sweet cordials, I was longing for some more virile drinks.” “His one thought, every day; was to return to his nocturnal peregrinations, either with his friends or alone and following the promptings of each new turn in the street. His meeting with Albert Plécy ; editor of Point de Vue – Images du Monde (yet another decisive encounter), did much to ensure the recognition of his evident talent. Plécy understood that Doisneau was not a standard reporter: he was something more and something else.

He appreciated the Doisneau style, as he called it, describing that universe as “moving, tender, more compassionate than grim, sometimes smiling, always ironic, never cruel.”

Throughout those intense and prolific years, more than fifty reportages, were published in Plecy’s weekly; which was then a current-affairs magazine. The subjects were as various as you like:

fashion, dance, the paranormal, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, nudists. the tattooed, Le Corbusier, Savignac. Among them were some of his most famous series: Le regard oblique (The Sidelong Glance) , Les Halles, The Woman-Accordionist, The Child and the Dove. Three of these reportages were taken up by Life magazine a month later. In addition to this work, he undertook several publicity campaigns for the car manufacturer Simca, which afforded him an opportunity to use color. But he also executed commissions for major companies such as Saint -Gobain, Orangina, and Sud Aviation and did illustration work: album covers, calendars, and in-house magazines such as Air France Revue, for which he worked regularly between 1950 and 1960.

This extraordinary outburst of diverse work made Doisneau’s name omnipresent and attracted the attention of the photographic world. His work was exhibited alongside that of Cartier-Bresson and Brassaï in French Photography Today in new York in 1948. Three years later, in 1951, he was one of the Five French Photographers at that city’s Museum of Modern Art, with Cartier Bresson, Brassai’, Edouard Boubat, and lzis. He even had his own solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954 under the title. Humoristic and Satirical Photographs of Paris. This international acclaim came in the wake of his reputation in France, where publishing was still expanding like wildfire and Doisneau had produced a number of books: Les parisiens, tels qu’ils sont, (1954), Instantanés de Paris (1955), and Pour que Paris soit (1956) with a text by Elsa Triolet.

In France, Doisneau took part in the creation of the Groupe des XV (1946), which brought together older photographers such as Lucien Lorelle and Emmanuel Sougez and a younger generation including Willy Ronis, Daniel Masclet, and René-Jacques. In 1956, the prix Niepce, founded by Albert Plécy and Les Gens d’Images to honor photographers whose oeuvre was particularly “remarkable” was awarded to him after stormy debates. It was also in 1950 that Life magazine commissioned from the Rapho agency a series of images illustrating Parisian lovers. This gave rise to the series of “kisses” that includes The Hotel de Ville Kiss, which has become for Doisneau what the The Angelus is to Jean-François Millet. These images, most of them staged, testify to his remarkable complicity with the actors of this typical Parisian performance, and were as successful in the United States as in France. Le Soir and Point de Vue both published the series, which is a faithful rendition of the gestures of true lovers against an authentic background.

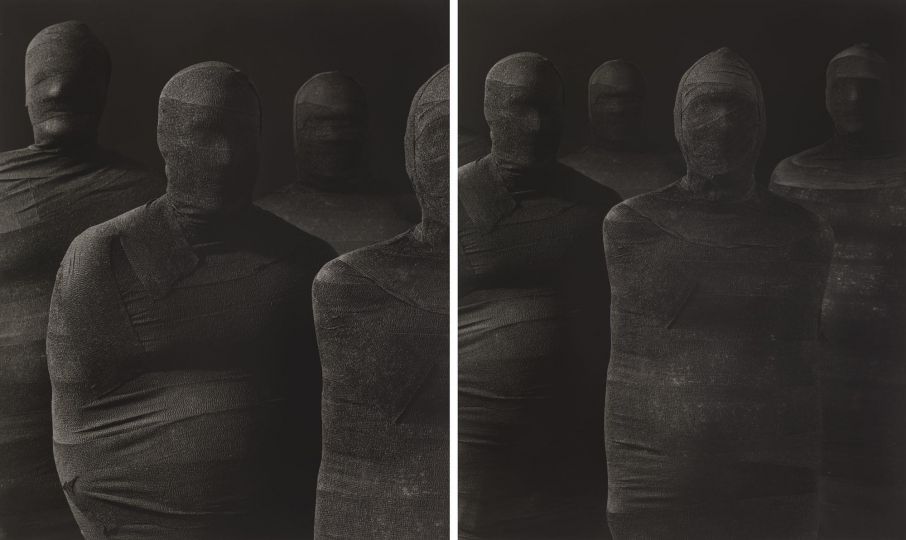

All these publications in dailies, magazines, and books combined with the exhibitions that accompanied them emphasize the quality and, above all, the diversity of Doisneau’s work. But these droll, witty, melancholy; or emotional photographs should not mask Doisneau’s other side: the socially committed photographer. This was a deeply rooted part of the man. But his attention to the condition of the working class was, predictably; given short shrift by publishers who preferred more conventional and light -hearted subjects. A closer analysis reveals that these images of miners and factoryworkers also constitute the most continuous and systematic element in Doisneau’s documentary corpus. He found in those worlds an echo of his own childhood and his sense of humanity and injustice. As he put it: ‘Human considerations, at that tine, were merely incongruous frills and furbelows that had no place in the galloping expansion of industry.”

There is a great deal to discover in these simple but profound images made in the mines of Lens and Moselle, in the foundries of Lorraine, or on the Renault production line. They are honest, testimonial images of the workplaces “where men serve out their sentence,” and there is no trace in them of a political message or photographic manipulation.

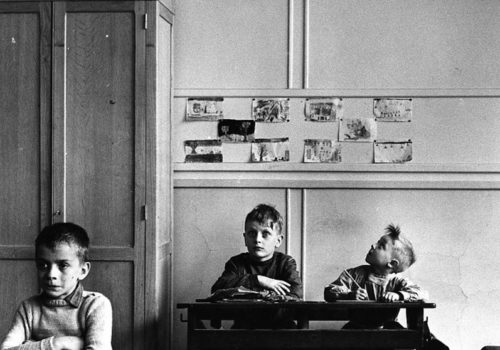

Doisneau’s interest in workers was not confined to the industrial world. His travels and commissions allowed him to keep company with railwaymen and deep-sea fishermen, cauliflower pickers and goose and duck farmers, sewermen and the shepherds of Haute Provence. During these tours of duty; which, he said, “lasted sometime for a day or two and rarely for a whole week, each time a visitor under pressure from his deadlines,” he created images that are sometimes sombre but suggest a powerful empathy and authenticity in his approach to the world of labor. It was a world to which he could not always give the attention that he wanted; family and economic needs had to come first. During this period of mercenary work, Doisneau was often overwhelmed with commissions, not all of which interested him, and he was thrilled when, making room between two obligations or “stealing’ time from his employers,” he could return to the Parisian suburbs and again “hang around on the streets and at last see people and their backgrounds, it [was] a respite in which my eyes [took] a greedy delight.” It was on these pedestrian expeditions that he captured many of the images that have since become iconic, such as Mademoiselle Anita, Monsieur Barre’s Merry- Go-Round, The Musical Butchers.

Doisneau’s reputation in France and abroad was at its height; his name had become synonymous with a certain kind of contemporary French photography Exhibitions proliferated in France and the United States. In addition to those already cited, he was represented in Otto Steinert’s subjektive jotografie (rgsr) and in Edward Steichen’s by now mythical exhibition, The Family of Man (1955), two landmark moments in photographic history Some years later, his name appeared in the first histories of photography; such as those by Helmut Gernsheim, Beaumont Newhall, or Peter Pollack.

“I never knew Atget, true, but he’s my godfather all the same. He’s a landmark as far as I’m concerned .. His photos somehow reassured me. “