To travelers and collectors, thangkas are vibrant paintings of deities, but to Tibetans, they are the buddhas themselves. Thangkas are a distinctly Tibetan form of art centered around religious figures and symbols. They are hand-painted by Tibetan artists and Buddhist monks who have devoted years to studying.

According to Tibetan lore, thangkas date back to the time of Sakyamuni Buddha. King Uttrayana of Dadok commissioned a painting of the Buddha as a gift to King Bimbisara of Magadha, but when the painters started to paint Sakyamuni Buddha, his holy light blinded them. They completed the painting by observing his reflection in water, and by capturing the Buddha’s reflection, the painters also captured some of his spirit.

Today, at least twenty thangkas are known to date back to the 11th and 12th centuries. The tradition is rooted in the early paintings surviving in the Ajanta Caves and Mogao Caves of China, where thangka painting developed alongside Buddhist wall paintings. The painting of thangkas spread wherever Tibetan Buddhism was practiced, including Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, Mongolia, and other parts of the Himalayas.

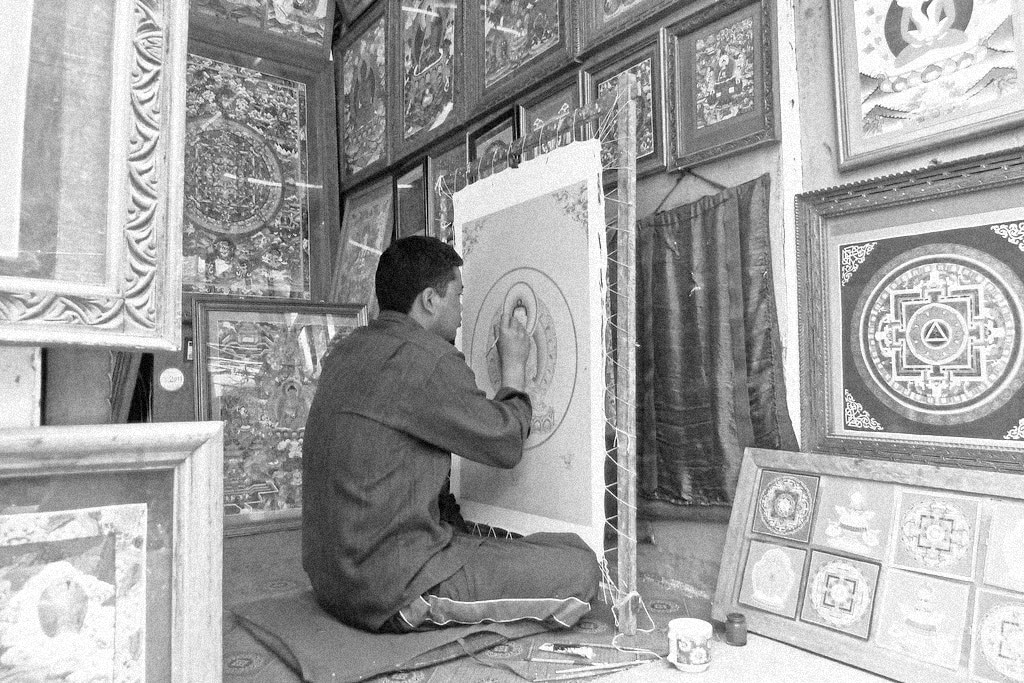

Thangkas usually depict religious figures such as Buddha, Buddhist deities, bodhisattvas (enlightened beings), and teachers. They can also depict Buddhist teachings, events, scripture, and symbols, such as the Bhavachakra (the Wheel of Life). When painting a thangka, it is crucial to depict deities in appropriate body postures (asanas), hand gestures (mudras), and proportions (iconometry). Upholding age-old traditions and painting each brushstroke with intention is important because thangkas are viewed as a form of visual scripture. It can take a painter years to learn the iconometrics, stories, and characteristics of different figures. While some elements of a thangka follow clear-cut rules, a painter has total creative freedom when it comes to other decorative elements such as landscapes and backgrounds.

Before a thangka is painted, painters first purify themselves and their environment by washing their hands and lighting incense. They stretch white fabric across a frame and apply white gesso (a type of primer) or chalk. They burnish the surface with a smooth stone, then outline the image in black or red ink, paint the background black or red, then add the central figure. Final touches are made as the painting is gilded or embellished with gold leaf and mounted on silk.

A thangka is not complete until the consecration ritual. Monks chant, pray, and invoke the deity depicted in the thangka. The deity’s eyes are “opened” as the pupils are painted, and the words om ah hum (body, mind, spirit) are inscribed on the back. Upon consecration, the thangka is not just a painting; it houses the spirit of the depicted deity.

With intricate designs that require hours of artistry, most thangkas are the work of many hands. They are commonly overseen by a master painter who oversees the production of the work and handles the intricate brushwork while allowing students to contribute. To satisfy the commercial demand, some thangkas intended for non-religious use are produced through a combination of hand painting and machine printing.

Today, thangkas are hung in monasteries and homes around the globe. They run the gamut from fine art commissioned by patrons and passed between generations to souvenirs mass-produced for backpackers. Travelers visiting Tibet or enclaves of Tibetan culture like India’s Dharamsala will find colorful thangkas lining the walls of souvenir shops and spilling into alleyways. The beauty of thangka paintings and the ease with which they are transported have made them highly sought-after among tourists. Although commercial production was initially frowned upon, that sentiment has evolved. Many Tibetans believe the commercialization of the thangka is beneficial because it sparks curiosity in Buddhism and paves the way for more people to embrace Buddhist teachings.

While thangkas make beautiful decorations, it’s important to remember that thangkas serve deeper purposes. They are made to be venerated and can aid in meditation or tantric practices. They have also been used to teach young monks, students, and laypeople about Buddhism and Traditional Tibetan Medicine. Last but not least, thangkas can be commissioned to positively influence the karma of someone who has passed away if done during the seven to forty-nine days it takes for reincarnation to take place.

Modern thangka artists continue to keep this sacred cultural tradition alive; they do so by believing that painting a deity remains an act of deep worship and upholding the notion that the power of a thangka lies in the heart of the practitioner painting it.

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

The Travelling Jacket

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

The Himalayan Cedar

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

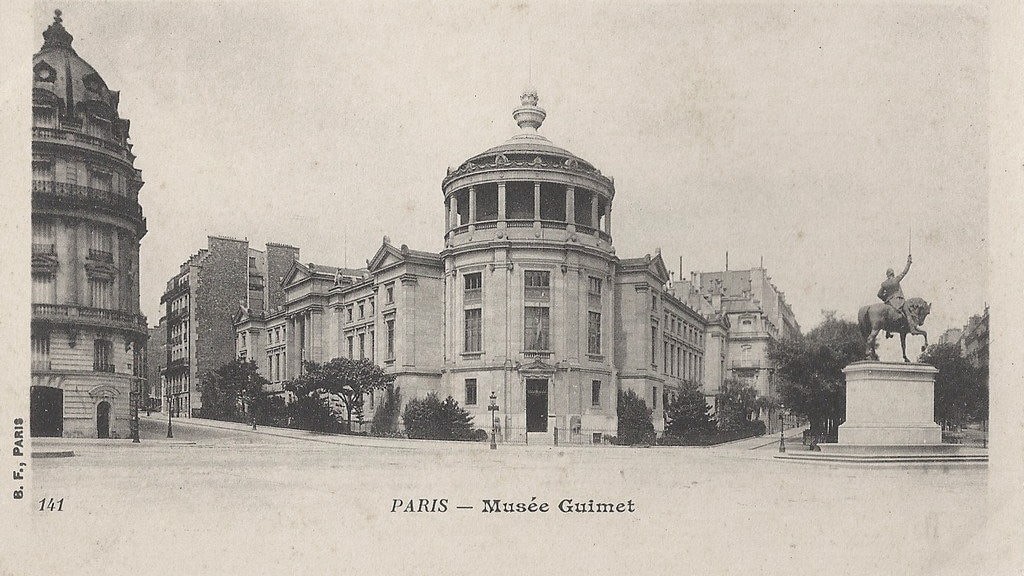

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.

Climate Change in the Himalayas

The region is warming rapidly in the face of climate change, complicating life for millions of residents.