Alec Soth Song of the Open Road

Siri Hustvedt

For his latest book, A Pound of Pictures, Alec Soth originally set out by car to follow the route of Abraham Lincoln’s 1865 funeral train, hoping to consider America’s current political division through the prism of a past historical crisis. When that idea felt forced, he let it go. But he kept driving. In Los Angeles, he encountered a woman who, to his astonishment, sold photographs by the pound. This discovery yielded compelling images of images and gave Soth a leitmotif: the weight of photography’s own history. For Soth, this weight was not a burden but rather a wellspring of connections and associations found in the surfaces of his surroundings and in his travels to cemeteries, darkrooms, and bedrooms that reference Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Nan Goldin, to name just a few touchstones that appear in the book.

In January, as yet another new COVID variant sent people back indoors, Soth spoke from his home in Minneapolis, via Zoom, with the writer Siri Hustvedt about the rhythms of narrative, Walt Whitman, and the democratic possibilities of sleep.

Siri Hustvedt: I thought we should focus on your most recent book, A Pound of Pictures (2022), in order to rein in our conversation a bit.

Alec Soth: What’s good about that is, it has a retrospective quality where I’m thinking about the medium.

SH: There is a real narrative pulse to this book. Even before opening it, the viewer-reader encounters a fairly long Whitmanian list on the cover. You establish a rhythm for what we’re going to see—an introduction to what I think is a crucial aspect of narrative: rhythm.

AS: Absolutely.

SH: Do you know this quote from Virginia Woolf? She was writing to Vita Sackville-West about literary style: “As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple matter; it is all rhythm.”

AS: That’s beautiful.

SH: I think the rhythmic foundations of narrative are corporeal and prelinguistic, but the way we imagine time in space is connected to literacy. The way we read images has a spatial component that acts as a metaphor for time. English speakers imagine time as a horizontal line moving from left to right. Arabic speakers imagine time going in the other direction. I read the other day that Mandarin speakers often imagine time as vertical. The cars in your pictures allude to a narrative journey, and they’re all going backward, that is, into the past.

AS: That’s an amazing way of looking at it.

SH: Every single car, except one. In the memorial image with the flowers on a street corner, there’s a parked car that’s headed into the future in terms of the spatial metaphor. And there’s the car with the bust of Lincoln, which is a quasi-comic image because it looks like he’s driving, and he’s headed for the past. I know from the book that Lincoln’s funeral was the original inspiration for taking the journey across the country and making these photographs.

AS: You are treating this as a book, which is beautiful. The book is, for me, the ultimate form for my work. But 99 percent of the people who see these pictures will see them in a different context, without that narrative. That’s part of my apprehension of investing too much in the narrative.

So, I have to try to make it function on different levels—for the ideal reader like you, who’s willing to look through the book in that sequential way versus the person who’s going to see one picture on a wall somewhere. That narrative functions differently when it’s internal to a photograph.

SH: But any image of a road implies motion, moving into the future or the past.

AS: The thing about the road, and the road trip, is it’s such a cliche, and I kind of hate it, yet I keep returning to it—process-wise it just works for me so well. But also, it’s a way to suggest narrative. So whether it be driving along the Mississippi River, or this imagined Lincoln funeral procession, that idea of a line moving in a direction helps.

SH: Another recurring image is of telephone lines. They extend beyond the frame of the photograph, so you’re led out of the picture, which also has narrative implications. And that can happen in a single picture.

AS: The thing that I always say about photography—and I think it’s true—is that it mostly just suggests narrative rather than gives you a story.

SH: Right, it’s not explicit. The meaning is made between the particular viewer and your photograph, but all viewers also carry larger cultural narratives, depending on where we come from and what we do. This is outside of A Pound of Pictures, but that image from Broken Manual (2010) with the school bus and the horse took me instantly back to the orange school bus I rode every day as a child in Minnesota. It’s an empty school bus. It’s not going anywhere.

I didn’t ride horses, but my sisters competed in rodeos and Western games. The combination, horse plus school bus, produced a plethora of personal meanings in me. But the photo also has the abstract, bizarre quality of some hypnagogic imagery. Do you see images before you go to sleep?

AS: Definitely in a napping situation, I have that. But with photography, it’s so utterly specific. That school bus and that horse and that place are so specific.

SH: The horse was really wandering by? You didn’t bring the horse over there?

AS: Oh, no. I absolutely didn’t bring the horse over there. My sense is it used the bus to protect itself from the wind or something. The hope is that someone will make that spark and launch off into some sort of imaginary space, or it could be from your own experience. I sometimes think of photographs as a diving board into a pool of imagination.

Let me ask you this. Would you agree with me that between the novel and the poem this difference in narrative is somewhat like the difference between a photograph and a film?

SH: Yes, although there are many possibilities. There are narrative poems, too. This book struck me as an elegy related to Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” which you quote in the book. There’s a repetition, a motion you establish of blooming flowers, especially yellow flowers, coming back.

AS: You got it! I found my audience.

SH: The famous lines—“Lilac and star and bird twined with the chant of my soul, / There in the fragrant pines and the cedars dusk and dim”—could be an epigraph for the book. There’s a lot of verdant foliage, but there are also, near the end, those desiccated individual blooms—stalks standing in front of the overgrown railroad tracks, which made me think of Lincoln’s funeral trip again.

AS: I’m just so happy that you get the book.

SH: The short Whitmanian list—lilac, bird, star—in an elegy for a dead man.

At the same time, the poem counters dying. Despite the death of the one he loved (he says, “for him I love”), there is burgeoning and blooming going on, and that snapping of the lilac branch. Whitman really is our great poet of democracy. He is continually leveling. My most beloved poem of his is “The Sleepers.”

I sometimes think of photographs as a diving board into a pool of imagination.

AS: Perfect.

SH: There sleep becomes the democratic force. That force is in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” too. But in this moment of pain and strife, the evocation ofWhitman’s elegy for Lincoln is particularly poignant.

AS: I like what you say about sleepers.

It makes me imagine a photography project in which, with all this political divisiveness, if you could just watch everyone sleeping...

SH: You do have sleeping people. Lots of sleepers and beds.

AS: There’s a lot of it. There is something about that state that does feel more forgiving or something.

SH: I think Whitman understood that deeply. As the poem goes on, it mounts to embrace all of humanity in this ideally American way with its promise of democracy, a promise that has never been fulfilled. But there’s another push in your book to represent representation itself. You make that clear right from the beginning. First, we see a cemetery with a photographer. Second, a blank easel. I looked very closely. I can’t find anything on the easel.

AS: Just the shadow.

SH: Just the shadow and the trees. The idea of representation and the presence of the photographer, whether it’s you or not, runs through the book. And we literally see piles of pictures. Other times mounted photos of really old pictures that are fading. I love the picture of a grave with a photograph. You can’t read the inscription, but the photograph is so clear. It’s a nineteenth-century photograph that nevertheless seems to have survived or been replaced...

AS: Stronger than stone. I don’t think it’s been replaced.

SH: And then, the little white flowers.

It’s beautiful, and it’s framed by the foliage.

AS: At a certain point, I made this connection between flowers and photographs. In photography, in my world, there’s this feeling that there are just way too many pictures, and we’re overwhelmed with them. Then I suddenly had this thought of, like, someone complaining about there being too many flowers. A flower is beautiful because it’s going to die. We think we take a photograph because it’s not going to die. It’s going to keep something alive. But it never works. And the photograph itself fades. But this connection with photographs and death, and then flowers and death too—that you would want to put a photograph on a grave. There’s something in that connection. One of my favorite pictures in the book is that woman with flowers on a street in Tulsa, and she’s got the tattoo.

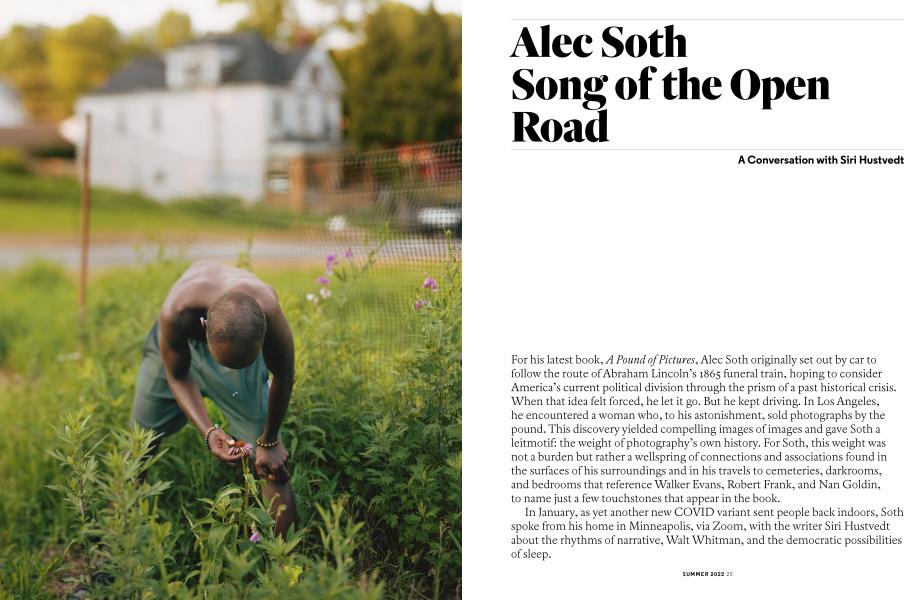

SH: The picture is fascinating. You focus on the woman even though she’s far away. There’s a tenderness about the way she’s handling the flowers, a kind of reverence that recurs throughout the book. There’s another picture of a young shirtless boy bending over a pink daisy-like flower. His gesture is so delicate and evokes what you’re saying— the transience of blooming—which is also in Whitman’s poem. And then winter arrives in your book.

AS: Maybe I should give you a little backstory in terms of the evolution of this book. As we’ve said, it started with the funeral train project. But then I had this idea that it was going to be a diary, hundreds of pictures intermixed with text, which is something I’ve never done. What happened was the pandemic hit, and so much happened in the world. It just felt impossible to then, a year later, pick up again with that diary format. During the pandemic, I forgot how to approach people and also got so in my head about: Oh, is it right for me to approach someone? What are the ethics of this? The political ramifications?

SH: You’ve talked about this before, and I think it’s important. You’re sensitive to the power dynamics involved in taking a photograph. I’ve had my picture taken for my work for over thirty years now. I’ve gone from pretty young thing to old lady. Especially when I was younger, but sometimes even now, I have felt emotionally and psychically assaulted by photographers. Photographs have a potential for cruelty that is real.

AS: Absolutely. For me, there’re two parts to it. There’s the taking of the picture, which nowadays is almost always a positive experience for me, and I think it is for the other person. I really try to have full consent, and I want them to be engaged and not afraid. And more often than not, they feel good about the experience. The problem comes in putting it on the wall and selling it for a bunch of money and putting it out in the world.

SH: I do feel that your work in general has a dialogical quality. The image of—

I think her name is Bonnie—she’s holding up a picture of a cloud angel. There’s integrity in her posture. She’s confronting you with this image. It’s almost as if the exchange between you two is present in the image. How is that visibly present?

AS: I definitely don’t have an answer for that. I am aware that people project onto these pictures a kind of intimacy that didn’t exist. Because I’m always told: “You’re so close with the people you photograph”—and I’m not. I know photographers who work that way, but I’m not that person. So, it’s this other kind of intimacy, hopefully.

SH: Writing about his work as a pediatrician, D. W. Winnicott said, “People need to be seen.”

AS: Oh, yeah. So true.

SH: This relates to your interest in connectivity. You have that nice John Berger quote about the constellations, which also relates to narrative—the only way we can see the bears in the sky is if we draw the lines.

AS: Yes. There aren’t bears in the sky.

SH: No. We make them there.

AS: They have meanings through the stories of the bears in the sky.

SH: You have talked about this publicly, but you had a transcendent experience in Finland?

AS: Yes.

SH: I have migraines with aura and have had a number of ecstatic experiences. We are hardly alone. Many people in these states feel boundaries dissolve and have a powerful sense that all things are connected.

I thought of this project as my ars poetica in photography. Trying to do something about the medium but in a lyrical way.

AS: What do you do with that knowledge in your art?

SH: In my novel The Blazing World,

I have a character named Sweet Autumn. She began as a comic character, a New Age kind of idiot.

As I was writing her and listening to her, she became bigger and bigger. She’s not the main character, but she’s given the last word because her ecstatic insights, which are very nonintellectual, are finally the most profound. She has synesthesia. I have mirror-touch synesthesia.

AS: It’s funny because I’m sitting here, looking right at you through Zoom— and you’re over there, actually at this enormous distance away, and we’re exchanging these words back and forth, trying to figure it out, to navigate this space between us. Which is exactly the way I think of my photography. What happened in that ecstatic moment was that that all kind of just fell away. It felt like there wasn’t that separation, and all these atoms, with my atoms mixed in, were all one thing. I found that problematic as a photographer, that photography was promoting separation in a funny way. But, of course, we don’t live in that ecstatic state.

SH: We all have to retreat to pedestrian reality and the boundaries that are part of it. John Dupre, a philosopher of biology, repeatedly stresses in his work that organisms are not things but processes. I would extrapolate— even in death, if you think about time as cyclical, there’s return—which is in your book. The graveyards, the earth, the dirt, the blooms returning in spring.

AS: I do think it’s that moment when you feel the thingness sort of start to dissolve, and the lines becoming blurry— a hypnagogic state.

SH: It’s like the weirdest kind of cinema entertainment.

AS: And there’s something about when I am immersed in my work that has a similar quality, where it’s a kind of hyperfocus to the point of things beginning to dissolve a little bit. Not in that ecstatic sort of way but a nice little version.

S H: I’ve been thinking that what is vital to artistic work is a state of physical relaxation accompanied by concentration.

AS: Well, that’s interesting.

SH: With relaxation you become open, and that openness allows both the world and unconscious presences and memories to act, to become available in ways that they’re not if you’re tense.

AS: The photographic act is really not relaxed for me. It’s quite tense.

SH: I guess you have to be arranging everything, don’t you?

AS: And I’m super tense when I’m doing it. But then there’s the other side, the daydreaming about what is this going to be about, what am I looking for, all of that— which is that relaxed state.

SH: Even though there are technical aspects that have to be fulfilled, none of that could happen if you weren’t in a state of openness to what you’re seeing.

AS: Right. And it’s achieving that state of openness. The thing about that list at the beginning of the book, it’s a way to say, hopefully, that this is open, that this is not a documentary about X.

SH: Exactly. And of course there’s that quote from Wallace Stevens’s poem “Of Modern Poetry” that you included there too...

AS: Oh, my gosh. You found that.

SH: Yeah, I love Stevens. When I was really young and writing, I used to have Wallace Stevens and Emily Dickinson and a few other people open on my desk because I thought they could send me signals and make me a better writer.

AS: I thought of this project as my version of an ars poetica in photography. Trying to do something about the medium but in a lyrical way. And that poem is such a great example of that. He is always this poet of consciousness. That’s a funny thing to want to aspire to in this clunky medium of photography, but I think there is a way to use it to address consciousness in some way.

SH: This is a great question. The mindbody problem.

AS: It’s so crazy.

SH: Consciousness is an unsolved problem. In your writing at the end of the book, you point out that a great deal of sensual information is missing from a photograph. You don’t hear birdsong, for example. No smells. This is true of all the arts. Even in film, the screen is flat.

AS: Right. But I think that lack of other information, or the peculiarity of just having a flat image, is what allows us to reflect on it.

SH: Oh, but that’s what’s so beautiful about it! And the fact that it’s silent. Photographs and paintings have this in common. You can stand in front of them, and you need time to take in what’s there, even though it’s there all at once. You can’t take something out or put something in once it’s done.

Lastly, I do feel there’s underground politics in the book, in that it’s related to what now appears to be the failing dream of democratic equality.

AS: I don’t know if that was my intention. That’s where I started—in that mindset. Then I felt like I was illustrating some idea about America. And once I broke free of that, I once again found positive, affirmative things out there. Because during the lockdown period, I thought, Wow, everything that I ever said about America is totally wrong. The whole thing is broken. And then, going out into the world and having some of these encounters made me think, Oh, it’s more complicated than that. That’s where I’m happy for other people to read into the pictures as they wish. How any of my work is interpreted about America tends to be highly charged in that way. That’s not how I think about it, but, of course, everything is political.

SH: Interpretation is a complex business. Agitprop and fierce rhetoric have their place in the world, but they’re not going to give you the complexity, richness, and ambiguity I like to feel from all the arts. And yet. the country is in desperate straits at the moment.

AS: That goes without saying.

SH: Ideology can create wooden, dead art. It has also inspired some stirring manifestos and extraordinary poetry.

AS: What I do love about Whitman, just to go back to where it all started, was that I found comfort in reading him at that moment. I was thinking about the Civil War and the assassination of Lincoln, and, like this moment, it was a pretty bad time. And then you have this guy who’s able to find all this beauty while still acknowledging everything that’s broken.

SH: He was a nurse, after all.

AS: Yeah, absolutely. He gave me a little bit of hope. He always does. And certainly, in terms of aspiring for more openness, he’s pretty good for that.

SH: Oh yes, he’s positively disinhibited,

I would say. And the list. The list. It’s the most democratic form you can find.

AS: Absolutely.

SH: Everything has equal value in a list.

AS: Walker Evans was a great list maker, and we think of his work as having that democratic quality as well. And photography is often called this democratic medium, in that it’s almost like list making in its visual representation—here’s a car, here’s

a street.

SH: Unlike a painting, a novel, or a movie, a photograph is of the world. Or that is what the viewer feels, right? There really was an orange school bus.

AS: There really was.

Siri Hustvedt is a novelist and scholar. Her most recent book is a collection of essays, Mothers. Fathers, and Others (2021).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue